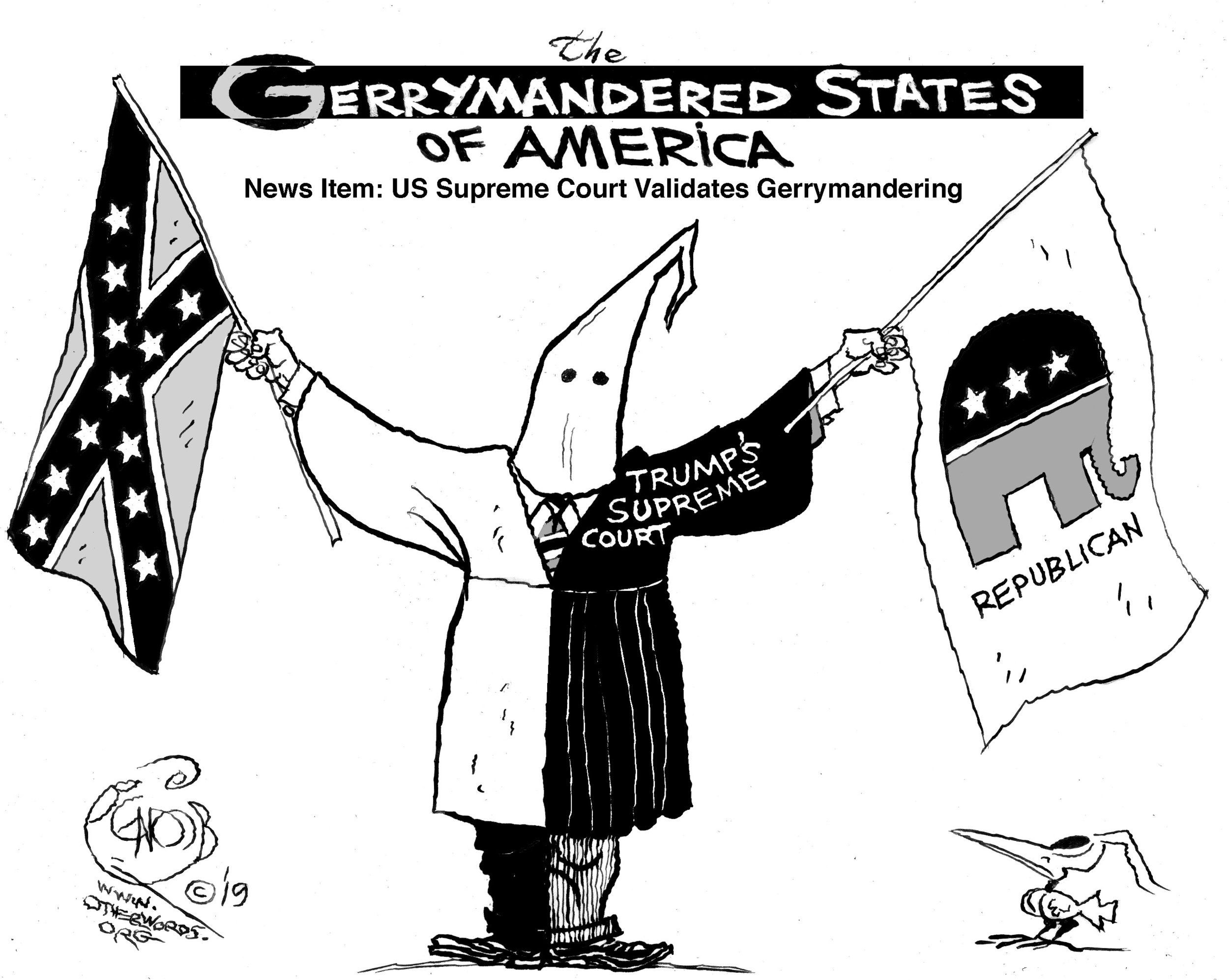

Gerrymandering is Another Way of Saying Election Theft. Republicans Now Have Scotus Backing Their Mugging of the Popular Vote

July 15, 2019

Interview by Janine Jackson

Janine Jackson: Partisan gerrymandering, in which one party manipulates voting district maps to increase its power, is “incompatible with democratic principles.” So declared Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts—but he and the Court’s conservative majority nevertheless ruled it’s a “political” matter, and not one for federal courts to consider.

Elena Kagan, in dissent from the ruling, Rucho v. Common Cause, wrote, “Of all times to abandon the Court’s duty to declare the law, this was not the one.”

Our guest says this ruling is just a part of a “power play,” employed overwhelmingly by Republicans, that seeks to narrow the metrics that determine how political power is allocated in the US political system. In other words, to suppress not just the political participation of, overwhelmingly, people of color, but the connection between participation and power.

How to report responsibly on such an important story? Steven Rosenfeld is editor and chief correspondent at Voting Booth, a project of the Independent Media Institute, and author of, most recently, Democracy Betrayed: How Superdelegates, Redistricting, Party Insiders and the Electoral College Rigged the 2016 Election. He joins us now by phone from St. Paul, Minnesota. Welcome back to CounterSpin, Steven Rosenfeld.

Steven Rosenfeld: Thank you very much. I’m so glad to be here.

JJ: When you were last here, in October of 2017, we were talking about Gill v. Whitford. That case focused on Wisconsin, where in 2012, Republicans won just 48.6 percent of the statewide vote, but nevertheless captured 60 out of 99 seats in the state assembly. And you described how this crafty redrawing of maps, combined with things like very strict voter-ID requirements, was adding up to Republicans getting a significant “starting-line advantage.”

If you say that a different way, voters aren’t really getting to choose candidates so much as candidates choosing their voters. It’s not hard to see how worrying this all is, whoever is doing it (and it’s, of course, overwhelmingly Republicans).

So the Supreme Court is now saying, “Well, yes, all of that is true. It is concerning. But if we were to intervene, that would be political.”

SR: Exactly.

JJ: So what should we make of that? And what does Samuel Alito have to do with it?

SR: What Samuel Alito has to do with it is, in that North Carolina case, which presaged the decision that’s come up very recently, is he was signaling that, basically, he was not going to get involved in this. They were basically saying the culture of politics is one where human nature and bad instincts can run wild, but it’s not the judicial branch’s role to balance that.

And actually, that’s exactly what happens in the Supreme Court decision there. And it’s also a sign of the times that this current Supreme Court—it’s not just this decision, but it’s going back recent years—is not going to get its hands involved in federal election regulations, checks, balances. And it’s almost as if—and I’ve been reading the law blogs, people are saying—they’re almost entering a period that’s like the early 20th century, where if you want to see progress on these issues, you have to look to the states.

And in some ways, that’s sort of what the Supreme Court just signaled. So you look to the states, where you get support for amendments to the Constitution for an equal rights amendment, or to change the vice president from being appointed to an elected office. So that’s kind of the big arc. And, as you know, state politics can be slow and messy. And that’s sort of where we are right now.

JJ: We’re looking at different points of intervention than we’re accustomed to thinking of, and I’ll bring you back to points of resistance.

I did want to draw on something you’ve written about recently. Folks did see this gerrymandering decision come down together with a ruling on the census, and the question of adding a question about citizenship to the 2020 Census. And in that case, the Court, surprisingly to some, in this Department of Commerce v. New York, they blocked the Trump administration from adding this transparently suppressive “Are you a citizen?” question from the census. But you wrote recently about how the Justice Department efforts on the census reveal a strategy that’s of a piece with what’s going on with gerrymandering, and it’s really part of a bigger picture.

SR: First of all, the census question is not dead.

JJ: Right.

SR: Because basically what the Supreme Court said is, they caught the administration basically in a lie, creating a false pretext. And basically said, “If you come back and tell the truth, and you give, perhaps, a partisan reason, that you don’t want these people to be counted for political purposes, maybe we’ll let it through.”

So what are we talking about here? What we’re really talking about are bottom line frames. You can talk about votes and seats. You could talk about starting-line advantages. What does that really mean?

Well, if people think back to before the 2018 election, we heard all about the blue wave, the blue wave. What does that really mean?

It means that these political parties know very well who their most reliable voters are. And basically, voters are segregated, when you draw these districts, so that one party, when they look—and the people who are the map makers, the map writers, this is their party—you take a look at your most reliable voters, who turn out in the years where you lost the worst.

So for this current decade, which is almost ending, we’re talking about the Republicans looking at who voted for John McCain in 2008, when Obama won by 10 million votes nationally.

JJ: Right.

SR: And you basically redraw your state legislative districts, and your congressional US House districts. So these are not statewide offices, this is not governor, this is not senator. And you take a look at who are the most reliable voters, and this is what the Republicans did in a dozen states; Democrats did it in one state where there was litigation, Maryland.

And you say, OK, we’re going to win with 46 or 48 percent of the vote as Republicans, and the Democrats are going to win with 69 or 70 or 71 or 72 percent.

So that’s how you get these supermajority legislatures, like the numbers you read in the beginning of this hour. You know, you have almost a 50/50 split. But you’ve got 65, 67, 70 percent Republicans; 30, 35 percent Democrats.

And you do it by putting lines on a map, where you draw around the most reliable voters in different parties’ bases. If you have a concentration of Democrats, it’s called cracking or packing; you split it up or you keep them together.

So what you end up having here, people have been very quantitative about this. So literally, the starting-line advantage in these highly gerrymandered, extreme gerrymandered states, Republicans have a 6, 7, 8, 9 percent—and it varies from state-to-state—starting-line advantage in a normal election year—not a crazy election year, everyone is passionate and turnout is high.

JJ: Right.

SR: You add on top of that other little nicks and sort of microaggressions, if you will, to undermine the turnout of your opponent’s base. And that’s where the voter ID stuff comes in. And that’s been shown by academics to knock off another 2 or 3 percent in turnout from a series of likely-Democratic groups.

Who are we talking about? The poor, students, older people, people from communities of color.

So what you had then—this was going into 2018—was literally, the Republicans had about a 10 percent, maybe a little bit more, of a likely-turnout advantage.

And that’s why we would see these polls, “Oh, the Democrats are up, you know, 15 percent!” But then come Election Day, it was so tight, but yes, a few of them sort of squeaked it out. Well, how could they be up so much in the polls, but just barely win on Election Day? It’s because the voters have been segregated.

And so where does the census question come in on this? The academic estimates are that in the communities that would be affected—now, this is not everywhere in America, but this is in certain communities, concentrations in blue states—approximately another 8 percent—we’re not talking about voters, we’re talking about the overall voting adult population—might not be counted.

JJ: Right, right.

SR: And then the way that translates into voting is, you also have these Republicans who are arguing that—and this goes back to the whole states’ rights thing—that the states should decide that they only want to count the voting age-eligible population. So again, that means not counting students, not counting children, not counting noncitizens, who are here either legally with visas or undocumented.

And all of this is designed to shape the electorate so that the people who are authoring these laws will retain political power.

And we know that the Republicans, which are primarily an aging white party, are getting diluted in an increasingly demographically diverse America. So this is what this is all about. And it’s not just map-making. It’s not just gerrymandering. We have seen, when Democratic governors have been elected in these states that have these supermajority red legislatures, like North Carolina or Wisconsin, the legislature will come back in—

JJ: Snatch back the victory, by undermining the powers of that official. Yep.

SR: So that’s just really what it’s all about. And what happens when you follow this stuff is, you could have a lot of technical explanations. Numbers and this and metrics and everything like that. But really, the bottom-line concepts, we’re talking about segregating the electorate, we’re talking about seats and votes, we’re talking about, who is the governing class? And are the rules being changed in the middle of the game?

And the Supreme Court has basically said, “We’re pulling back. We’re not going to touch this stuff. We’re going to revert to an era of states’ rights.”

All your listeners I’m sure know, “states’ rights” is a big synonym for what was the South under Jim Crow. Over the course of our lives, you don’t like the clock to go backwards. But that’s kind of what it is.

JJ: I just want to underscore that point about restricting the census to voting-eligible people. The census determines where hospitals are, and how roads are built, so you’re going to say, “Oh, no, we’re not going to include children. We’re not gonna include students.” I just want to be sure folks see the deep impact of—

SR: And let’s be really clear about this: The people who are the intellectual authors of this idea of going to a citizen, voting-age population, these are the people who brought the suits against affirmative action in university admissions. “This is a race-free America.” Unfortunately, we’re not a race-free America.

JJ: No!

SR: And the people who tend to win out when you remove these forms of balancing tend to be white, entrenched majorities. This didn’t come out of nowhere. These folks have been fighting for years. And it’s pretty nasty stuff, quite frankly.

JJ: Let’s move on to the question, or back to it, because you talked about where pushback can be and is, which is at different levels, is at the state and local level.

So I don’t want to let folks think that nothing is being done. There is work being done.

What can be done in terms of practical resistance to the impacts of these democracy-distorting kinds of moves?

SR: It comes at the census and redistricting. What happens is, after the census every 10 years—although some states rush this calendar, and that’s a political decision—[states] redraw their district lines. And the fairest possible process is taking it out of the legislatures and having these citizen or bipartisan redistricting commissions.

So if you’re in a state where that is a possibility, that is the best path to go. And by the way, in some states where people have pushed for that, in Michigan, Democrats pushing for that, the Republicans have tried to stop it. Again, it’s just really brazen power-grab stuff.

But when it comes to the big picture here, what you’re talking about are some microaggressions, like voter ID, and things that are a little more macro, like have these starting-line advantages.

The only thing that people can do to basically get past all this is to turn out and vote in large enough numbers, so the wave swamps these basic microaggressions’ nickel-and-diming of the process.

And that’s all we’ve got. That really is all we’ve got. And we saw it in 2018, where there was historic turnout, and hopefully there’ll be historic turnout in 2020. And hopefully we’ll have transparent vote counts and audit trails, so people can believe the results.

Because one thing about the Republicans is, they have no hesitation to play dirty, and fight as hard as they possibly can to stay in power. And we’ve seen it again and again and again. We saw with blocking the Supreme Court nominee in Obama’s last year of his term. We’re seeing it in the census question. So you just have to look at this stuff realistically, and call it what it is.

JJ: We’ve been speaking with Steven Rosenfeld; he’s editor and chief correspondent at Voting Booth, that’s a project of the Independent Media Institute. His most recent book is Democracy Betrayed: How Superdelegates, Redistricting, Party Insiders and the Electoral College Rigged the 2016 Election. If you want to find the Voting Booth work, it’s online at IndependentMediaInstitute.org.

Steven Rosenfeld, thank you very much for joining us this week on CounterSpin.

SR: Thank you so much. It’s a real pleasure.

Posted with permission

BuzzFlash Note: Due to gerrymandering in Wisconsin — in the 2018 election for the state assembly — 54 percent of the popular voters supported Democratic candidates, but the Republicans ended up maintaining their 63-seat majority. Only 36 Democrats were elected to the assembly. Meanwhile, the Democrats swept all the statewide offices, but still were in the minority in the state assembly and senate. This is just one example of the nefarious anti-democracy impact of GOP gerrymandering in one state.

Obama won the 2008 presidential election vote in North Carolina, but after redistricting by a Republican general assembly following the 2010 census the districts were gerrymandered to favor the GOP. Indeed, in 2012, the Democrats beat the GOP by nearly two percentage points in the total vote for US Representatives. However, the North Carolina Congressional delegation in 2012, due to Republican gerrymandering, resulted in only four Democratic Congressional Reps as compared to nine GOP Reps. Remember, that the total Democratic vote for NC Congressional Reps was won by Dems, but the gerrymandered districting resulted in a more than 2-1 GOP majority in NC’s congressional delegation.

The 5-4 decision by the Supreme Court this June sent the North Carolina gerrymandering of state legislative and US congressional districts back to lower courts. This means that unless state courts, which are often partisan toward Republicans in Republican states, demand an end to gerrymandering, it will continue to result in defying the will of the voters and preserve an inflated white GOP congressional delegation in Republican states where the state houses and governorships are in GOP hands.